His Mantra: “We Gotta Do Something!”

<video at the bottom of this page>

Mike Cox likes to joke that he started out as a “country bumpkin” from rural Washington State. But by 2017, after 25 years at the Environmental Protection Agency, he was in national headlines. His scathing resignation letter to new EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt went viral, landing him on CNBC and in major national outlets.

I didn’t know any of that when I met Mike on Bainbridge Island’s Climate Change Advisory Committee in 2021. He had just led the development of a 140-page climate action plan and seemed involved in nearly every environmental effort on the island. Curious what fueled his tireless drive, I sat down with him in September 2025 to find out.

Work Ethic and Widening Perspective

Mike grew up in Walla Walla, Washington. His father, a small-town doctor, worked long hours, often leaving dinner to make house calls. His mother died when Mike was 19, and his father four years later. “I was left with nothing,” he said. “I had to figure it out on my own. The one thing I carried forward was: you work.”

His worldview broadened on a 28-day Outward Bound trip in Oregon’s Three Sisters Wilderness, which included people from very different backgrounds. It ended with a three-day solo beside a river with no food or tent. “By the end,” he said, “I felt like I had fully melded into the natural world.”

At the University of Puget Sound, an Environmental Studies class opened his perspective further. “We learned we’re part of all of this [the natural world], but we’re manipulating it in ways that aren’t good—creating inequities that aren’t fair.” He later transferred to Western Washington University’s Huxley School of Environmental Studies, where he learned about global issues like poverty and hunger and met students from all over the U.S. that wanted to make a difference. “It was invigorating,” he said. “I realized this is what I wanted to dedicate myself to.”

Five Years in Africa

After college, Mike wanted to see what he’d studied. So, he joined the Peace Corps in Malawi, Africa as a math and biology teacher. Poverty, he said, “was right there staring you in the face every day when you walked out the door. I knew I could leave… and they couldn’t. It didn’t seem fair. These were good people, and I left feeling like I needed to do stuff that might help.”

After earning a graduate degree in public health from the University of Michigan, Mike joined the EPA in Washington, D.C. Four years later, he and his new wife, Barbara, returned to Africa—this time to Togo—where he worked with UNICEF building latrines and wells. “I never had a harder job,” he admitted. The work was rewarding but grueling. They considered staying indefinitely but ultimately returned home, believing they could have a bigger impact in the U.S. Still, Africa left a deep impression, sharpening his conviction: we gotta do something.

25 Years at the EPA

That conviction led Mike to a long and impactful career at the EPA, with a few of those years at the City of Seattle’s Sustainability Office. In D.C., he led teams developing national drinking water regulations for contaminants like lead and disinfection byproducts. Later, in Seattle, he headed the regional drinking water program and then managed the region’s scientists. One of his most meaningful achievements was bringing scientists directly into the policymaking process.

In his final five years, Mike served as Climate Change Advisor for the Northwest region, working with states, tribes, farmers, and local governments. “I had to learn to communicate with people on their own terms, with their own values,” he said. “It wasn’t just about the science—it was about trust and respect.”

His career ended dramatically in 2017, when he resigned after Pruitt’s appointment. “For me, it was about integrity,” he said. “Protecting people’s health and our environment is too important to compromise. At some point, you have to stand up and say what’s right and what’s wrong.”

That moment confirmed what he had always believed: environmental protection isn’t just about science or policy—it’s about values.

Bringing It Home

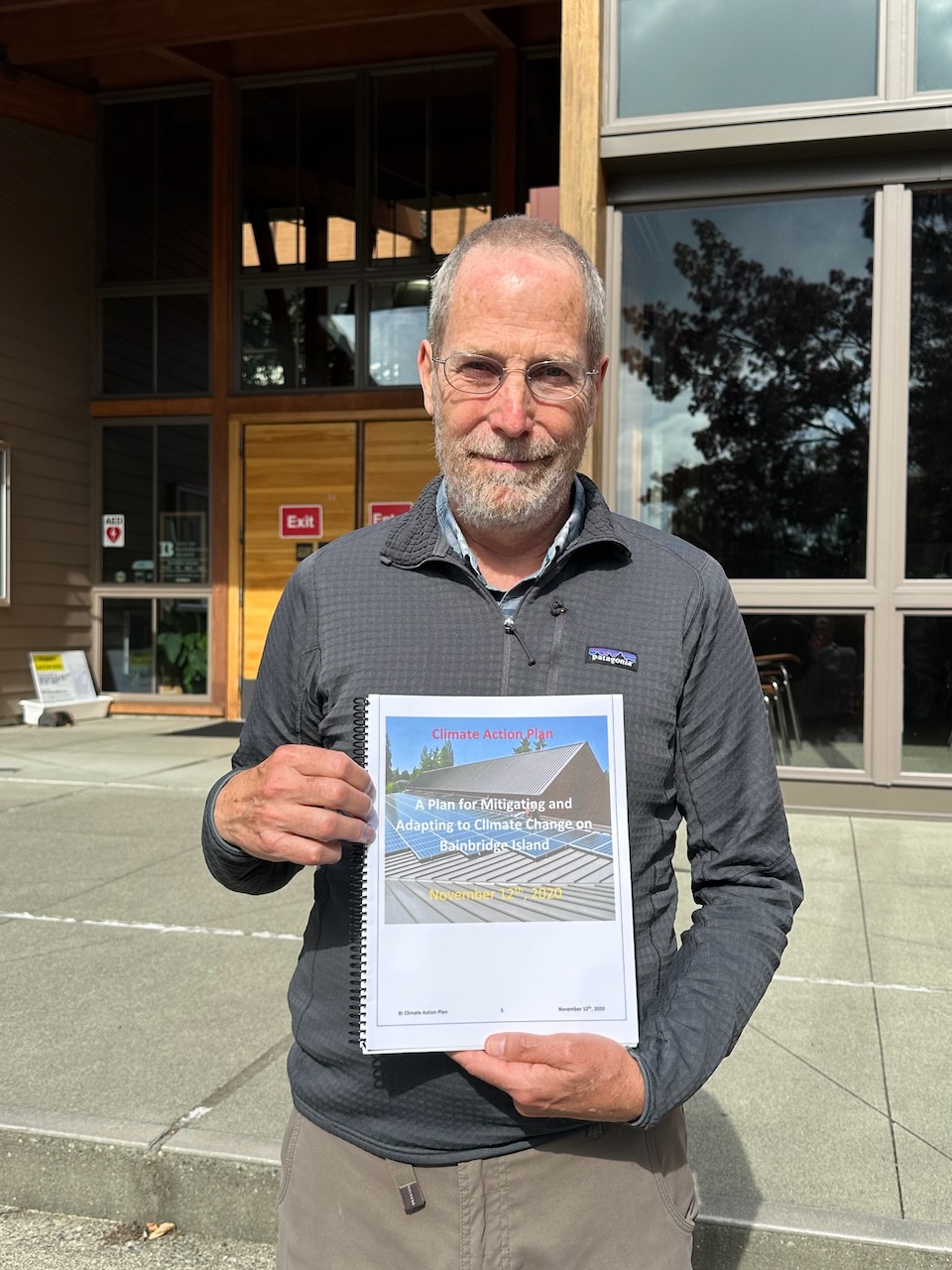

After leaving the EPA, Mike didn’t slow down. He poured his energy into his hometown of Bainbridge Island. He helped start the city’s Climate Change Advisory Committee and led the development of the island’s comprehensive climate action plan (link below). He also co-chairs Climate Action Bainbridge, started the Interfaith Council Climate Circle, and helps organize numerous local climate-related events.

By my rough count, he’s logged more than 10,000 volunteer hours since retiring. When I asked why, he shrugged. “This is where I live, and this is where I can make the most difference. It’s not glamorous, but it matters. Local action adds up.”

He also feels a quiet urgency: most of his family died relatively young. “It makes me feel like I’m racing against the clock,” he said.

A Philosophy of Service and Fairness

What drives Mike isn’t just an appreciation of nature but a deeper philosophy about how to live.

- Obligation to give back. “It’s internal. If I don’t do it, I feel selfish. It’s gotta be done.”

- Fairness and justice. “The people who contribute the least to climate change are often the ones who suffer the most. That’s not fair, and we can’t ignore it.”

- Future generations. His two sons and his new granddaughter shape his long-term perspective: “I want to set an example and leave something better behind.”

- Stoic influence. He draws on Stoicism: focus on what you can control, not what you can’t. “It keeps me grounded.”

- Faith in connection. Though not religious, he believes deeply that humans are part of the web of life—and responsible for caring for it.

These values explain both his stand at the EPA and his tireless local commitment today.

Finding Hope Amid Challenge

Mike is honest about the emotional toll of climate work. “It’s easy to get discouraged,” he said. “Some days it feels like we’re not moving fast enough.” But he stays motivated by small wins, building community, and seeing younger generations step up.

Hope, to him, isn’t naïve optimism. It’s the resolve to keep going because the stakes are too high to do otherwise. He also takes inspiration from Pope Francis’ Laudato si’, which frames environmental stewardship as both a moral and spiritual duty. “The way he framed it really resonates for me,” Mike said.

Lessons from Mike’s Journey

From rural Washington to African villages, from EPA offices to Bainbridge Island town halls, Mike Cox’s path has been remarkably consistent: use your skills in service of something larger than yourself. His story shows that protecting the environment is not only technical or political—it is moral.

Not everyone will resign in protest or lead a climate committee. But his journey offers a clear takeaway: each of us has the ability—and the responsibility—to contribute in whatever ways we can.

Links & Resources

Article: “EPA scientist sends scorching letter, retires with a bang” (2017)

Leave a comment